The 150 year old diplomatic relationship between Venezuela and the Holy See has been marked by ups and downs.

Relations were first established in 1869, but they were not officially formalized until 12 years later. In 1918, the Vatican officially opened its nunciature in Caracas.

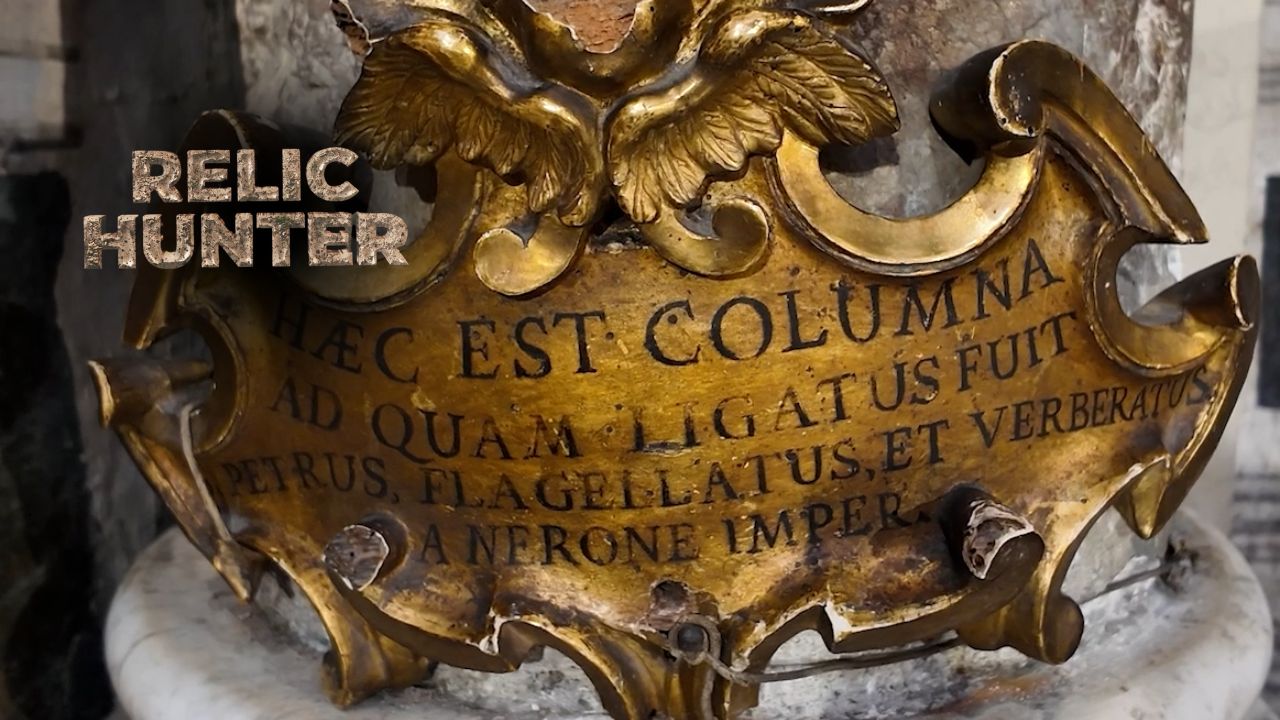

But there was a deep issue in the relationship until 1964: a law titled Ecclesiastical Patronage was in force. Derived from the Spanish era, it allowed the State to control the Church, meaning it could, for example, propose or veto bishops.

To abolish it, an agreement was signed in 1964 with the Holy See, guaranteeing the Church full freedom and allowing the Pope alone to choose the bishops.

Diplomatic relations were relatively stable from then on. Pope St. John Paul II traveled to Venezuela twice—in 1985 and 1996—and through these trips offered pastoral support to both the clergy and lay faithful alike.

Only three years after the second papal visit, in 1999, Chávez came to power. He encountered a Church with full institutional autonomy and one he could not control. The relation between the church and state in Venezuela began devolving.

HUGO CHÁVEZ

Well, may the devil receive you into his bosom, monsignors… I make the sign of the cross like this, in the name of us, the true Christians. You are not Christians—no way.

Relations worsened further when tensions arose over appointments of new cardinals. Chávez naturally had his own candidates in mind.

HUGO CHÁVEZ

I had my candidate—and he’s neither someone subordinate to me nor a Chavista… He’s a monsignor who should be a Venezuelan super-cardinal. His name is Mario Moronta.

Bishop Moronta maintained a friendship with Chávez, but he was a firm opponent of Nicolás Maduro’s regime and was overall a well-respected figure in Venezuela.

When he died in 2025, Cardinal Porras described him as “a devoted shepherd and faithful witness of the Gospel.” Opposition leader María Corina Machado described him as “a man of unshakable faith, intelligent and kind.”

Bishop Moronta never received the red biretta. In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI instead made Jorge Urosa Savino a cardinal at his first consistory.

That had been in March, just two months before Chávez traveled to the Vatican to meet the German Pope during his European tour. At that time, Chávez was entering a phase of radicalization, and the Venezuelan Church had been highly critical of his government.

The simultaneous decision to elevate Urosa to the College of Cardinal upset Chávez even more, souring the relationship further. He was not a fan of the new cardinal.

HUGO CHÁVEZ

Now this cardinal comes out because the squalids and the yankees send him here to try to scare the people by talking about communism—that communism has arrived. Hey, he’s a troglodyte.

He not only spoke out against the clergy in Venezuela, but directly targeted the validity of the Vatican.

HUGO CHÁVEZ

With all due respect to the State of the Vatican and the head of state of the Vatican, who is the pope—who is not some ambassador of Christ on Earth, as they say… For the love of God… What is this ‘ambassador of Christ’? Christ doesn’t need an ambassador. Christ is in the people.

Besides Chávez, there were also other familiar faces present: Maduro and Cilia Flores. All of this happened at the height of confrontation with the Church, around 2010.

CILIA FLORES

We are going to continue denouncing and exposing these false prophets, and it won’t be with a cassock that they’ll be able to deceive this people—no one will ever deceive them again.

The Venezuelan Bishops’ Conference spoke out about Chávez’s constitutional reforms but with great caution. The bishops warned that his plan would put the people’s religious and social freedoms at risk.

Chávez even called for changing the 1964 Venezuela–Holy See agreement. He justified the change by saying the Church had too many privileges and accused Cardinal Urosa of interfering in politics.

HUGO CHÁVEZ

I announced—and we’re going to do it—a review of the agreement that Rómulo Betancourt signed somewhat secretly, it wasn’t properly discussed and the country didn’t even find out, between the government of Venezuela and the State of the Vatican, which gives certain prerogatives to the top leadership of the Catholic Church.

We are not going to accept that this cardinal and these bishops, using their religious authority, trample on the dignity of the Venezuelan people.

But the 1964 agreement remains in force. Despite threats to change the agreement, it has never yet been altered or repealed—neither after Chávez’s death nor after Maduro came to power.

CA